Like to go to Art Galleries? I do.

When I was in Europe this past spring, I visited a lot of them.

Second question. Do you appreciate every painting you see in a gallery? Probably not – some attract us and others will not.

I was thinking about this in some of the major galleries I visited. I waited in a long line to get into one famous gallery in Frankfurt, Germany. They had on display many well-known masterpieces. I was delighted to get to see them in person. I also noticed there were paintings that I didn’t like and didn’t want to give more than a passing glance. I wondered about my neglect of them, thinking I was probably missing something. The curators who selected them out of many others they could have put up must have seen something in the work I wasn’t appreciating.

After all, I’m not an art connoisseur. This summer, I was reminded of my lack of artistic sophistication visiting the National Gallery in Washington DC with a childhood friend who teaches Art History. She helped me recognize dimensions of meaning in what we were seeing that I had missed.

That said, I’ve also noticed some paintings and sculptures have more universal appeal. Like that strange smile on the Mona Lisa’s face that fascinates people, some of the works I saw on my travels had people gathered around studying them, sitting nearby and contemplating them. These works had a dimension that the other ones didn’t seem to have; a dimension that spoke to something deep within them.

Whether a painting or a beautiful song, an other-worldly meal, or a smell that awakens powerful memories, our senses can give us access to the depths of our being; access to the sources of our faith through direct personal experience.

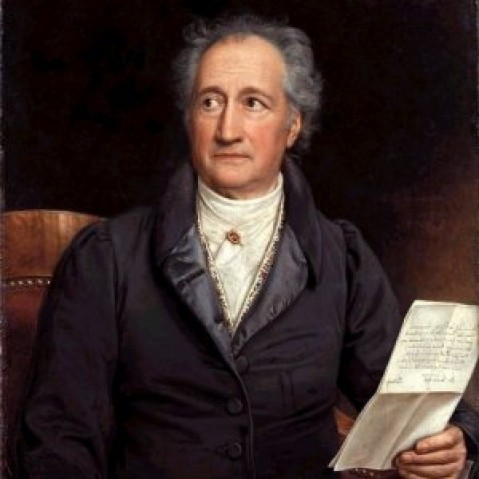

With Joann Wolfgang von Goethe’s help, we’ll explore this process with a quote from his writings:

Simple Imitation, Manner, Style by Goethe (1789)

Imitation

Assume that an aspiring artist with some talent begins to paint natural objects after only brief preliminary training in basic techniques. He copies forms with care and diligence and imitates colors as closely as he can, taking pains never to deviate from nature, beginning and completing every picture with an eye to nature. This person will always be an estimable artist because he will necessarily achieve an incredible degree of accuracy, and his works will be assured, vital and diverse.

If we analyze such a course of development carefully, we are led to the conclusion that this method is suitable for a capable but limited talent in treating pleasant but limited subjects…This type of imitation would, then, be pursued by calm, conscientious persons of moderate talent who paint still-lifes.

Manner

However, such a technique is usually too pedantic or inadequate for the artist. He perceives in a multitude of subjects a unifying harmony which he can only reproduce in painting by sacrificing details. He is impatient with drawing letter by letter what nature spells out for him. He invents his own method, creates his own language to express in his own way what he has grasped with his soul. As a result he gives a distinctive form to an object that he has often copied, without now actually seeing it before him or even recalling exactly what it looked like in nature.

Now his art has become a language that expresses his spirit directly and characteristically. And just as anyone who thinks for himself will order and formulate his ideas on moral issues differently from others, so any such artist will see, apprehend and imitate the world differently. He will approach the things of the world with a greater or lesser degree of deliberateness or spontaneity and will accordingly recreate them with circumspection or with casualness… [Individual] elements must be sacrificed if the general character of the whole is to be adequately expressed, as for example in landscapes…

Style

Through imitation of nature, through the effort of creating a general language, through painstaking and thorough study of diverse subject matter, the artist finally reaches the point where he becomes increasingly familiar with the characteristic and essential features of things. He will now be able to see some order in the multiplicity of appearances and learn to juxtapose and recreate distinct and characteristic forms. Then art will have reached its highest possible level, which is style and equal to the highest achievement of mankind.

While simple imitation therefore depends on a tranquil and affectionate view of life, manner is a reflection of the ease and competence with which the subject is treated. Style, however, rests on the most fundamental principle of cognition, on the essence of things.

Sermon

I enjoy taking photographs. I’ve enjoyed photography since I was a small child when I got my first brownie box camera. I did video production in high school. But I neglected this interest after I graduated and through the 1980’s. I got back into taking pictures after our son Andrew was born in 1992. I got a fancy Sony 8mm video camera and recorded a great deal of his early life. Sadly, art is often in the eye of the beholder. Much as Philomena and I get teary eyed watching these videos, our son Andrew is far more jaded. I’m not sure if he will want to keep them after both of us are dead. This is why we need grandchildren, at some point, who, I hope, will be interested in them and want to save them for posterity.

I spent a little time looking back over my collection of photographs this week looking for some stellar ones I might be able to show you that are magnificent works of art. Can’t say I found much that might meet Goethe’s standards unfortunately. Still, as I looked through the pictures, I noticed some had more depth and power than others, beyond stimulating my sense of sentimentality (which is pretty strong by the way). The ones I found the most interesting were the ones of people, particularly those who are no longer among the living, especially the pictures that expressed, in some way, a distinctive element of their personality.

Another factor, however, in my response to viewing them, might be an experience of looking at my old pictures with new eyes. That new way of looking started with my visit to Goethe’s house in Wiemar, Germany during my sabbatical time in Europe this past spring. Because I don’t speak German, I discovered the easiest way for me to learn about and appreciate German culture was by experiencing German art, sculpture and architecture.

My sister lives in Jena which is the next small city over to the east from Wiemar, both in what was the former East Germany. Wiemar has a long and interesting history including being the home to the Bauhaus movement. Goethe arrived there in 1775 at the invitation of the young Duke Carl August, prince of the Saxony-Weimar city state. The Duke became a patron of the young artist/poet/lawyer whose first novel titled The Sorrows of Young Werther had recently become an overnight sensation.

Goethe collected an enormous amount of art for the Duke and himself, some of which is on display in his house. During the tour, we walked past plaster replicas of famous Greek and Roman sculpture. The tour guide explained that Goethe was so taken with the classical art he saw on a trip to Italy, that he wanted to have them in his home so he could contemplate them. By seeing the art again and again, he could discover more and more about the art and deepen his appreciation and understanding of the pieces. For Goethe, access to the divine, to the eternal, could come through being an art connoisseur.

This approach to art both surprised, interested, and challenged me. As someone who has not spent a lot of my life contemplating or creating visual art, the manner and style aspects that Goethe wrote about wasn’t familiar to me. So I set about looking for more information than the tour guide could offer or was supplied in the museum next to his house. This search hasn’t been very easy as Google didn’t give me what I was looking for. I’m grateful to have a good university library here that did help me discover what I was looking for.

The piece of Goethe’s writing I found I’d like to share with you is a dialogue between an artistic advocate of innovative approaches to theater scenery and a resistant spectator who wants the scenery to appear true to life. After all, the spectator observes in the dialogue, great pains are taken to create the scenery and costumes to recreate a particular period and setting to transport us through the realism. The advocate challenges the spectator to think about going to the opera. Yes, realistic scenery and costumes might suggest a time and place … but in real life, do people walk around singing all the time? Do they fight singing and die singing? That is hardly realistic. >>>

Yet, rather than feeling deluded, real emotions and familiar situations are communicated that feel authentic and transport us into the story, to the point of rapture if the production is done well. So, even though outwardly the art may not be true to life, it communicates an inner logic we recognize as a great work of art. Goethe makes his point in the closing words of the advocate:

“A great work of art is a work of the human mind, and thus also a work of nature. But because the work of art treats its diverse subject matter as a unified whole and reveals the significance and dignity of even the most ordinary subjects, it goes beyond nature. A work of art can only be comprehended by a mind that has been formed and developed harmoniously, because only such a mind can relate to what is excellent and complete within itself. The average art lover has no concept of that. He treats the work of art like a piece of merchandise. But the true connoisseur sees not only the realism of what is imitated but also the excellence in the selection of subject matter, the imaginativeness in composition, and the supra-natural spirit of this micro-world of art. He feels that he must rise to the level of the artist in order to enjoy the work, that he must focus his scattered energies on the work of art, that he must live with it, must see it again and again, and thus achieve a higher level of awareness.” (from On Realism in Art 1798)

Only through the highest artistic development of style, as described by Goethe in the reading, do we achieve a quality of art that gives us access to the greater depths of reality, to truth, goodness and beauty, that are expressions of the divine in forms comprehensible to humanity. Yet not everyone can recognize these deeper dimensions. Some can only see the surface appearance of the art, take pleasure in the resemblance to reality and miss the rest. Others go inward and notice the effect the art has on them and begins to see the connections between the parts. Only the educated connoisseur of style can use the art as a doorway to the divine, to the infinite depths of meaning embedded in a masterpiece.

Of course the visual arts need not be the only way to access these artistic depths. Many of us have musical pieces that we can listen to over and over that continue to speak to us in novel ways. Sacred church music, like some classical requiems, and masses can do that for me. I know others of you have favorite operas that connect you with eternal themes of living and dying. Great architecture that we experience again and again can also speak to our depths. Even flavors of a masterfully prepared meal can transport us to a higher level of being.

Another, more immediate artistic expression comes to us through movement. From the outer beauty of dancers in perfect synchronization to the inward journey of self-discovery in a yoga pose, the body can express our inner life more effectively than words can. This past week, I was at a workshop for UU ministers learning to move with coaching from an acting instructor. The way he moved his body as he worked with us, enthralled me with its expressive power, cultivated, I’m sure, over many years of training. He was able to move in a way I didn’t need to hear his words to know what was spontaneously happening inside him.

Okay, so if art, music, and movement are such engaging ways to connect with the depths of existence, why are sermons the central focus for our Sunday services? Why are we so dependent on words to reach for the ineffable?

Unitarian Universalism has inherited a discomfort with religious artistic expression through our Protestant heritage. A big part of the schism with Catholicism 500 years ago was over how we should be in relationship with the divine. Should it be through the Church … or through the Bible? These reformers rejected Catholic sculpture, art, architecture, sacred music and liturgy for the revealed word. “Solo Scriptorium,” Scripture alone they cried. All we need to be saved and serve the Lord will be found in the holy word. People shouldn’t get their religion from statues, stained glass windows and Stations of the Cross. They need to learn to read it for themselves and have unmediated access to truth; access not manipulated to serve the Church’s agendas, say selling indulgences to get your dead relatives into heaven that then financed opulent splendor in Rome. In that context, art became a tool of oppression against the masses.

Institutionally, Unitarianism and Universalism inherited this suspicion of sacred artistic expression. Our Puritan forbears whom we rejected, weren’t the greatest art lovers – more the opposite. They were fearful of art’s ability to stimulate lustful feelings and intemperate behavior. Puritans wanted their followers to focus their minds on God rather than the sinful world. While we changed our theology, we only started questioning our reliance on words in the twentieth century.

My purpose today is not to criticize or denigrate the power of words to inspire us. My purpose is to expand our appreciation for the arts as a way to enrich and enliven our religious life. Matt, Leah and I worked together with Thandeka a couple of years ago to enhance our access to emotion during our services. I’m wondering this morning if our austere Puritan heritage is still hanging on to us.

I wonder if we honor our senses enough as sources of inspiration. While we still value worship spaces like this one for their ability to lift up our spirits, today many of us would be happy to worship in a quiet forest or on a beach or on a mountain top as well as we might here in Emerson Community Hall. A candle lit bedroom with soft music playing as two lovers embrace can be as holy a space as a high pulpit. And religious ritual, in a spacious cathedral filled with iconic art and sacred music, can stimulate erotic, ecstatic feelings that make us feel a sense of being one with the holy. We need not make a division between the sacred and the secular

That said, I’m wondering today if others of you, like me, have neglected the role of art as a doorway through which we can develop our religious lives. That visit to Goethe’s home woke me up to a sensual dimension of my faith I was neglecting. What I’ve noticed looking around the walls in my office is the need to change what I’m displaying that is not inspiring me as I look at the pictures…. Not that there is anything wrong with my art on the office walls mind you. They just don’t have the quality of style that Goethe talks about.

If you look around your walls at home, you may have the same experience.

So my challenge for you today is to reflect on your relationship with the arts, particularly the visual arts. Do you relate to it as mere ornamentation or representation? Or does it function in a deeper way in your life; in a way that could feed your growth and development? What kinds of changes might introduce this artistic dimension to your life? Something as simple as putting some great art on your computer desktop; adding a provocative painting to your wall; possibly finding a spot for a replica of a great classic Greek or Roman Statue might be a way to begin to contemplate it and explore the deeper meanings art could have for your life.

Whatever you do or don’t do, remember that our spiritual lives are nourished by far more than words alone. All the world’s scriptures are not enough. We need our senses too, to nourish our faith.

Benediction

I close with this Goethe quote:

One who possesses art and science has religion;

One who does not possess them, needs religion.

May our appreciation of art

as the highest development of our senses

Help guide the growth and development of our faith.